The Decline of Traditional Hostelling.

A long-standing friend and accountant, Tim Kingcott, introduced me to Youth Hostelling in 1985, when he, along with another friend, Keith White, and I stayed at Totland Bay Youth Hostel at West Wight. However, after my first experience there, I returned home with some reservations. After travelling across Europe, the Middle East, and the North American Continent for the past thirteen years, I had always stayed in a hotel room and enjoyed the privacy of the night sleeping alone. And nobody had ever told me it was time for bed, either!

What I had found off-putting about the idea of hostelling, and particularly the Totland Bay Hostel, was precise that - the warden's announcement that it was time for lights out. For an adult in his thirties, this was basically an insult. As far as I'm aware, a child is told it's time for bed, not an adult. Then added to that was the mandatory chore assigned to every hosteller by the warden.

|

| Bruges, Belgium, 1987. |

Mine was hand-washing all the evening meal dishes, quite a big task lasting the better part of thirty minutes, whilst Tim and Keith shared in the drying and the packing away. You may wonder: Why did I find the mandatory duty unsettling?

As stated last week, these duties involved mainly cleaning in one way or another - which happens to be my full-time occupation. In principle, I have always believed that a manual task is good for the well-being of one who sits at a desk all day - whether at school, college or work. I have also read what psychologists and psychiatrists say, that pushing a broom, hoovering the carpet, or even emulsifying a room could aid in beating depression or even combatting mental illness. Indeed, for someone who is academically minded, shovelling snow in the winter most likely will do him some good. But for me, as a window cleaner, the idea of going on holiday or taking a break was to be free from such full-time responsibility. However, in the years to come, YHA England & Wales was about to see some changes.

The average age of the hosteller increased throughout the late eighties and into the nineties. As older people began to replace the school-agers, they tend to have more money in their pockets, and therefore less keen on the mandatory duty "to keep running costs down." The 1985 Totland Bay experience looked to me to have been the charity's last attempt to keep the system compatible with school-age youngsters arriving from urban sprawl and retain the title of Youth Hostel.

All the hostellers at Totland Bay were adults of varying ages. At the same time, the YHA was beginning to feel under threat. That threat was realised when the YHA began closing their hostels and selling off the property that housed them. Winchester was one of them, and up north, Chester also closed. And Totland Bay itself was soon deleted from the map. And several more, one after another. Indeed, unless some house rules were changed, the whole charity would eventually go under.

Patrons no longer considered themselves as youths. They were generally older and more independently-minded. They had money and were willing to pay a little more, enough to scrap the mandatory duty but still pay less than a hired hotel room if they were to sleep in a dormitory. And I was around to see these changes - such changes eventually motivated me to use the hostel rather than a hotel as a base for both cross-country and international travel.

|

| At Ghent, Belgium, 1987. |

It was during the nineties and looking through some travel magazines, especially Trailfinders, that I saw that this decline of the YHA was happening on a global scale. It was about that time when an umbrella organisation, Hostelling International, or HI, was formed to administer each nation's particular YHA. Countries included in this scheme were the countries of Western Europe, the USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the UK with YHA England & Wales, Scottish or SYHA, and YHA Northern Ireland.

In each edition of Trailfinders, YHA New Zealand had the approximate words blazing out of its advert page: WELCOME TO OUR HOSTELS IN NEW ZEALAND: NO DUTIES. This says it all. Youth Hostels Associations around the world were attracting clientele who were older, more independent, and ready to boycott the charity if their hostels still insisted on the chores. Hence, to stay afloat, the clientele was no longer from a school in the city. Rather they were backpackers arriving from as far as halfway around the world. In turn, the Warden became the Receptionist and the hostel itself became the Backpacker's Hostel, but the initial for Youth was retained to keep the YHA logo recognisable.

In Australia, their YHA-affiliated hostels didn't go all the way as New Zealand, instead, they held the Dollar-or-Duty scheme. To anyone other than one with an ultra-tight budget, everyone else, including me, was willing to pay the extra Australian dollar. At the time, I never bothered to calculate that if I were to spend every night at a hostel for six weeks, the additional expense would have totalled A$42 - enough at the time for a full week's grocery shopping for two or even for a family. A student on a gap year break would have paid an extra A$360 to avoid a daily chore for the whole year. Yet, I never thought that way and neither did the other backpackers, as the majority of Australian hostels in 1997 simply assumed that we weren't interested in carrying out any duties.

|

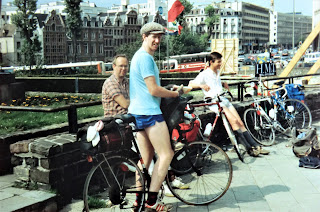

| Here, I'm with Gareth, Keith, and Tim, 1987. |

In America, their HI AYHA, along with HI Canada, had in 1997 a popular rival across the continent: Rucksackers North America with their Banana Bungalow Hostels, based mostly in California but also found elsewhere across the more touristy areas of the States back then. With such a popular rival, the AYHA had long withdrawn their mandatory duties as they watched their clientele flock to the more casual Banana Bungalow with its no-curfew stance and even parties stretching into the night. In 1997, at one non-affiliated privately-owned hostel at Hervey Bay, Queensland, backpackers who, during the day would hike a trail or gaze at the corals of the Great Barrier Reef, were that night dancing in the hostel bar to loud music with even some of them dancing on the large, sturdy tables. I didn't. Instead, I just sat there and watched, wondering how a YHA hostel in Southern England would have thought!

In contrast to this, there was one American hostel where I had to do a mandatory duty, and that was a HI AYHA-affiliated hostel in Pheonix, Arizona. For the record, this was the only hostel duty I ever carried out outside the UK. And that was on my 43rd birthday, of all days! This task was to wipe down the inside of a shower cubicle. It only took five minutes, yet, it was not much of a birthday present.

International Hostelling gets Underway - with Friends.

The decline of the duty and the rise of adult membership in both the UK hostels and those around the rest of the world was enough for me to eventually swap the privacy of a hotel room for that of a hostel dormitory. And there were swings and roundabouts. The advantage proved a benefit for the budget. Hostelling had opened the door for much longer holidays. The longest continuous time spent backpacking outside the UK was ten weeks from June to August 1997 whilst on a Round-the-World trip. That wouldn't have been possible had I stayed in hotels or even American motels. So, what was the secret? The member's kitchen is found in all hostels whether affiliated with the YHA or not. Buying my own groceries saved me from the expense of restaurants and even coffee bars. Then cooking the food in a communal kitchen was the epicentre for meeting people and forming new friendships.

|

| A bit of playful banter in Belgium with Gareth and Keith. |

The downside was the lack of privacy. And this reared its ugly head in several ways. One was during the night whilst sharing the dormitory with a loud snorer. The remedy for this, out of trial and error, was to make temporary earplugs from a double sheet of toilet tissue, two adjoining sheets for each ear to prevent the plug from going too far in the canal, and soaked in water before insertion. Despite the slight discomfort, this made quite a difference and allowed me to sleep soundly despite the loud snore.

The late eighties were quite different from the past travelling experiences. Instead of travelling on my own, I started to team up with four other eager friends. All five of us were single, all of us attended a church regularly, and all of us were keen cyclists, with me with the added credentials of a triathlete. One rider was Paul Hunt, an architectural assistant, and who already had a girlfriend back home, Kelly. Then there was Gareth Phillips, a banker. Next was Keith White, at the time a kitchen porter, and Tim Kingcott the accountant. Finally, I was a self-employed window cleaner who completed the group. As I saw it, this interclass mix on the social level was a wonderful ethic, a demonstration that acceptance and friendship were not based on our status, occupation or level of education.

In 1987, we loaded our bikes onto a train at Liverpool Street Station for Harwich port, from where a ferry sailed us to the Hook of Holland. We then spent a week cycling through Holland, into Belgium, and then into Germany, where we turned around at Cologne (that is, Koln in German). We stayed at hostels throughout the trip and for the first time, at Amsterdam our first overnight stop, none of us was assigned a duty by the warden. We talked about it and at first, we simply assumed that duties were non-existent on the Continent, or simply in Holland. Or was the duty confined only to the UK?

We didn't use the member's kitchen (if there was one there.) Instead, a buffet was accessible and we chose our own food items for breakfast. And this seems to be the norm of all the hostels we visited in all three countries. No duty, no member's kitchen and a buffet service for breakfast. As for other meals and refreshments, we relied on restaurants, adding extra expense to the holiday.

I found Brussels, in many ways, to be a twin sister of London with very similar architecture. I was curious when we arrived at Brussels Central Station, housed in a large building. Thinking that it was the city terminus, Gareth and I went downstairs, underground, only to find that this was a through station.

But Brussels, to my opinion, wasn't the loveliest city we stopped at, even if we spent a night at the hostel in the capital. Rather, I think the prettiest town in Belgium was Bruges, where we spent a night at a hostel there.

|

| Tim, Gareth and Paul at Ghent. |

In Germany, we spent at least two nights at the city's Deutz hostel, a loud, chaotic venue. One morning, after breakfast at the buffet, we returned to our dormitory - only to find that all the cash was missing from my wallet, even though my credit and debit cards were intact. With no traveller's cheques, rather than mess around using my banking cards in a foreign country, all my mates gave me a share of their cash, and until the end of the trip, I was able to live on their generosity. This a reminder of when my traveller's cheques were stolen whilst on the train from Pisa to Florence six years earlier in 1981.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Next Week: More Adventures with Friends.

twice your finances no no not good

ReplyDeleteDear Frank, What a frightening thought -- to have your cash stolen while traveling! But praise the Lord for the companionship, caring and generosity of your friends!

ReplyDeleteHaving access to a kitchen while traveling is certainly handy and can definitely cut down on eating expenses. But one of the joys of travel is experiencing new cuisines and restaurants! If we go on a weekend trip, we usually eat out, but if we're staying somewhere for a week, we definitely prefer a kitchen, for snacks, some breakfasts, and the option of cooking for some meals.

May God bless you and Alex,

Laurie